How to Deal with High Altitude Sickness

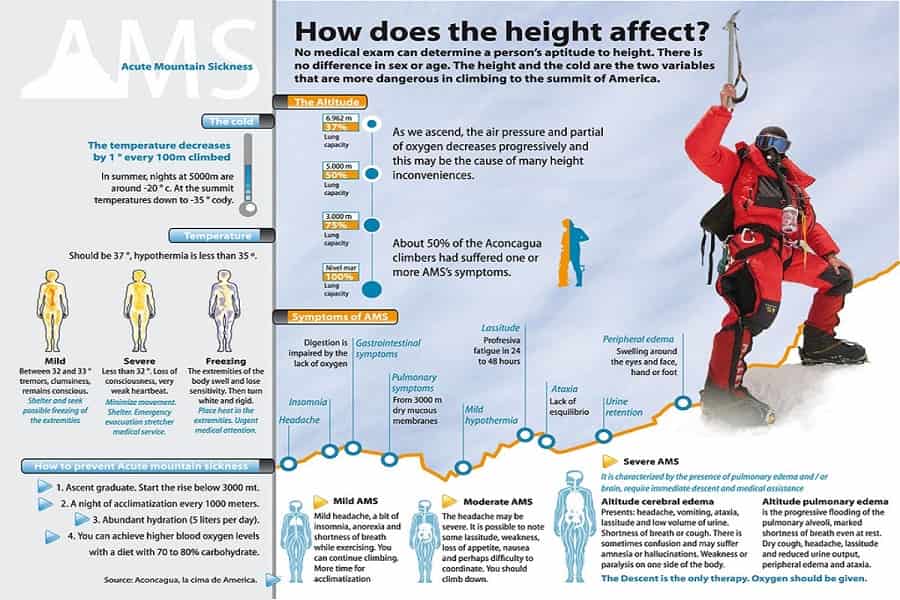

Acclimatization as related to mountaineering is the adjustment of the body to the varied climatic and environmental changes encountered at the higher altitudes. The concentration of oxygen at the higher altitudes remains the same; however the pressure decreases exponentially. Thus the saturation of oxygen in the hemoglobin reduces. The result is deprivation of oxygen to essential parts of the body. The most common form of illness due to lack of acclimatization is acute mountain sickness (mild, moderate or severe AMS). Everyone experiences varying degrees of mountain sickness at altitudes higher than 2000 m. The most common symptoms are headaches, nausea, vomiting, dehydration, loss of appetite and sleep among others. Severe cases include High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). Here fluid starts accumulating in the lungs and brains respectively.

The body starts to adjust to the lack of oxygen by increasing breathing rate, producing more red blood cells, faster heart beat, and suppressing certain non-essential functions. The period of adjustment varies from a few days to few weeks. For permanent adjustment, the period of acclimatization varies from months to a few years.

Various studies have been carried out on acclimatization, and the effects of high altitudes on the human body. The results have often been inconclusive, and contradictory. The following is a guide for the novice on the art of acclimatization based on the experience of seasoned and veteran mountaineers:

Symptoms of mild AMS is common for almost all people who encounter the high altitudes for the first time. A period of at least 3 days is to be spent initially at the beginning of the trek, with light activity to get used to the environment. A common maxim among mountaineers has been ‘Climb high, Sleep low’. Ideally in the trek you would want to climb to a higher altitude during the day and sleep at a lower altitude during the night. This has proven to be beneficial in most cases. Also it is recommended that the climb in a single day be not more than a 2000 ft gain and there be a rest day interspersed for every 1000 m gain especially if one is climbing beyond 5000 m. The traveler must ensure sufficient liquid intake throughout the trek to avoid dehydration. Certain medicines like Diamox, Dexamethasone, Ibuprofen and Nifedipine are found to be helpful and commonly stocked for the treks. These medicines are not without a list of side-effects and can generally be avoided. However they are used in emergency situations and as prescribed by a medical professional.

Mild AMS is common as said earlier, and trekkers can continue the journey after proper acclimatization. However in the case of the severe AMS, HAPE, and HACE, it is pertinent that the trek is aborted and the affected people be brought to lower altitudes. HAPE and HACE are potentially fatal conditions.

It is to be remembered that acclimatization is not directly related to the physical fitness of the participant. Even physically fit people can suffer from AMS due to improper acclimatization. Also different people respond to the change in altitude differently. The rate of acclimatization and the symptoms vary from person to person.

The following are the important factors that affect the acclimatization process: – (1) Rate of ascent (2) Altitude attained (3) Length of exposure (4) Level of exertion (5) Hydration and diet (6) Inherent physiological susceptibility.

In summary the easiest way to acclimatize is :- (1) Gain height slowly (2) Climb High, Sleep Low (3) High Carbohydrate diet (4) Hydrate. It is best to perform some simple low altitude treks to acclimatize, and also realize the individual body capacity and reaction, before performing the intended trek.